Definition

Universal jurisdiction

The principle of universal jurisdiction provides for a state’s jurisdiction over crimes against international law even when the crimes did not occur on that state's territory.

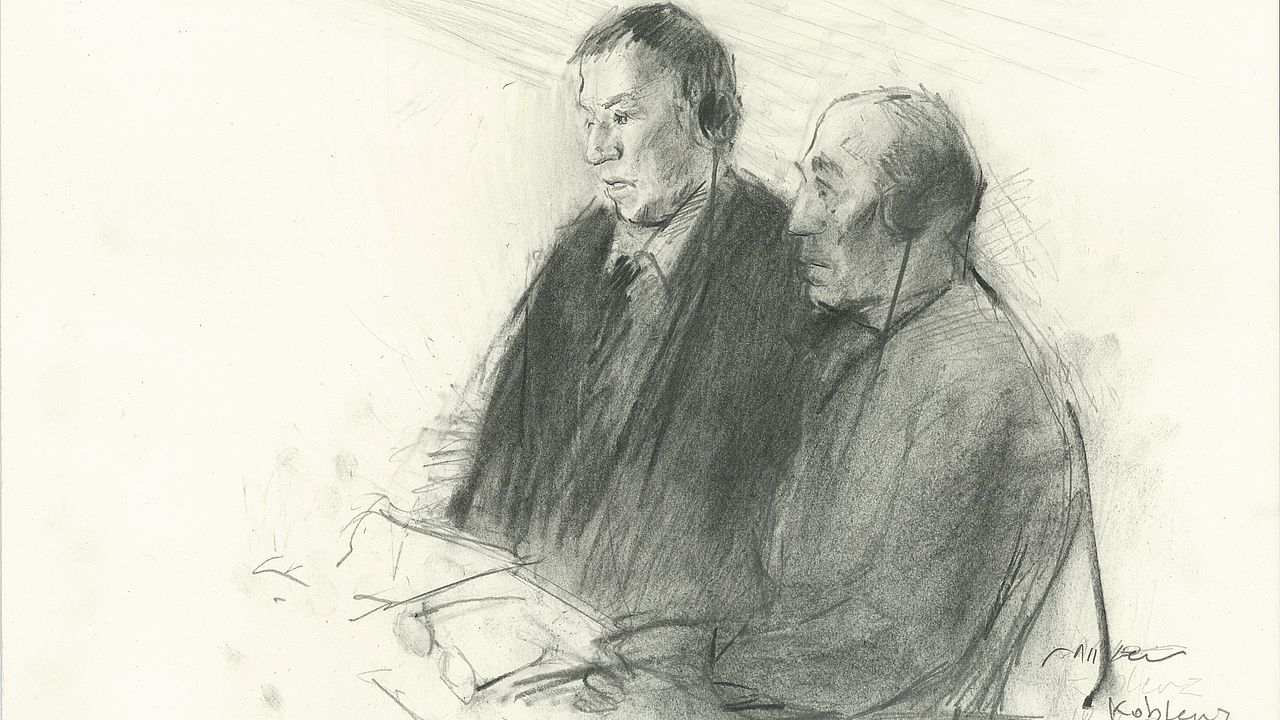

Show MoreThe first trial worldwide on state torture in Syria started in Germany in April 2020. The defendants: Anwar R and Eyad A, two former officials of President Bashar al-Assad’s security apparatus. In February 2020, the Koblenz Higher Regional Court sentenced Eyad A to four and half years in prison, and in January 2022, the conviction of Anwar R followed.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office charged Anwar R and Eyad A with crimes against humanity in October 2019. ECCHR supported 29 Syrian torture survivors in the so-called al-Khatib proceedings, 14 of whom were joint plaintiffs. We also published trial updates after every day of the proceedings.

In January 2022, the Koblenz court for the first time convicted a senior Assad government official for crimes against humanity in Syria, Anwar R, to a life-long sentence. The court found him guilty of being the co-perpetrator of torture, 27 murders and cases of sexual violence and other crimes in the al-Khatib Branch. Already in February 2021, the court sentenced Anwar R’s associate, Eyad A, to four and a half years in prison for aiding and abetting 30 cases of crimes against humanity.

“This process in Germany gives hope, even if everything takes a long time and nothing happens tomorrow, or even the day after tomorrow. The fact that it continues at all gives us as survivors hope for justice. I am ready to testify,” said a Syrian who was tortured in the al-Khatib detention facility.

Testimony from witnesses supported by ECCHR contributed to the German Federal Supreme Court issuing arrest warrants for Anwar R and Eyad A in February 2018.

The trial in Koblenz is also the result of a series of criminal complaints regarding torture in Syria, which ECCHR and nearly 100 Syrian torture survivors, relatives, activists and lawyers filed since 2016 in Germany, Austria, Sweden and Norway.

In June 2018, the German Federal Court of Justice issued an arrest warrant for Jamil Hassan, which can be enforced internationally. Hasssan headed the Syrian Air Force Intelligence until July 2019. ECCHR and its Syrian partners’ submissions to the Federal Prosecutor’s Office played an important role in that case as well.

Unfortunately, this media is unavailable due to your cookie settings. Please visit our Privacy Policy page to adjust your preferences.

Q&A on the legal background of the case

In January 2022, the Koblenz Higher Regional Court sentenced Anwar R to life in prison for crimes against humanity. R was found guilty of as a co-perpetrator of torture, 27 murders, dangerous bodily harm and sexual violence, among other crimes.

The court already sentenced Eyad A in February 2021 to four years and six months in prison for aiding and abetting torture due to his involvement in a “rapid intervention force in the field” that was deployed to crackdown on demonstrations.

For many of those affected, the fact that Anwar R was pronounced guilty of sexual violence as a crime against humanity was an important milestone. ECCHR partner lawyers successfully petitioned the court to prosecute sexual violence not as individual cases but, rather, as a systematic crime against the Syrian civilian population.

The verdict on Eyad A became final in April 2022, but a decision has not yet been reached regarding the appeal filed by Anwar R against the verdict in his trial.

The Syrian regime has violently suppressed opposition activities critical of the government since at least April 2011. The Syrian secret services (Air Force Intelligence, Military Intelligence, General Intelligence Directorate and Political Security) played a central role in this. The government’s aim has been to stop the protest movement at the earliest possible stage and intimidate the civilian population. Anwar R and Eyad A worked for the Syrian General Intelligence Service, specifically at Branch 251, which is responsible for the Damascus area.

The case was heard before the Koblenz Higher Regional Court because Eyad A was arrested in Rhineland-Palatinate, over which the Koblenz court has jurisdiction. Alternatively, the German Federal Prosecutor’s Office could have filed charges at the Higher Regional Court in Berlin, where Anwar R was arrested. Due to the close connection between their content, the two cases were linked together.

Since 2011, the Federal Public Prosecutor has been investigating several individuals in connection with crimes committed in Syria, as well as conducting a structural investigation (Strukturermittlungsverfahren) to examine the overall situation in Syria and the systematic nature of the crimes committed there. Beginning in 2017, ECCHR, together with nearly 100 Syrian torture survivors, relatives, activists and lawyers in Germany, Austria, Sweden and Norway, submitted a series of criminal complaints concerning torture in Syria that contributed to the investigations.

These preliminary investigations provided the basis of the al-Khatib trial.

The al-Khatib trial in Koblenz was based on the principle of universal jurisdiction. According to this principle, which was enshrined in the German Code of Crimes against International Law (CCAIL) in 2002, grave crimes like genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity do not only affect individuals and specific countries, but the international community as a whole. If states in proximity to the crime or international legal forums are unavailable for criminal prosecution, universal jurisdiction offers an alternative path to prosecution. This allows Germany (and other states where the principle is applied) to prosecute international crimes regardless of who commits them, where they are committed, or who they are committed against.

Syria is not a state party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Therefore, the only way for the ICC to have jurisdiction over Syria is by referral from a UN Security Council resolution. Such a resolution was vetoed by China and Russia, preventing the ICC or a special tribunal from taking action. This means that for the time being, the only proceedings possible outside of Syria are those that invoke the principle of universal jurisdiction in third states, or where third states can claim jurisdiction because one of their nationals was involved in a crime as a victim or perpetrator.

This was the first trial worldwide on crimes against humanity committed by the Syrian regime and was therefore of considerable international importance. In the proceedings, the Koblenz court also provided an overall picture of the political situation in Syria and the system of interlocking security services that have violently oppressed the population since the rule of former President Hafiz al-Assad. The focus of the trial, however, remained on the crimes of the Syrian regime since the beginning of the revolution, with a particular emphasis on the crimes of the General Intelligence Service within the so-called al-Khatib Branch. For the first time, legal evidence was gathered and presented within a judicial context. In future trials, whether at the national or international level, it will be possible to draw upon this body of evidence.

The trial was thus a crucial first step on the long road to justice in Syria and has helped to make Syrian crimes and their impacts visible.

The trial also provided a chance for Syrian torture survivors to convey their experiences within a courtroom and to actively contribute to the efforts to bring justice to Syria. The proceedings also played an important role for those whose relatives were killed in prison or are stilled imprisoned within detention facilities.

Witnesses testify in court because they have information relevant to the trial, but were not necessarily personally affected by the crimes charged. In the al-Khatib trial, witnesses have been heard who, for example, knew either of the accused individuals or could recount the circumstances of the repression of the protest movement in Syria.

A joint plaintiff is a party to the proceedings. Only those who personally suffered or are still suffering from one or more of the crimes charged can request to become a plaintiff in the trial. In the al-Khatib trial, plaintiffs included not only survivors of torture or sexual violence, but also the relatives of those were killed. If admitted by the court, plaintiffs have certain procedural rights and can, for example, pose questions, give statements and request the admittance of evidence. Several plaintiffs in the trial made use of their rights in the form of closing statements, in which they conveyed their perspectives on the proceedings.

Survivors and witnesses of human rights violations are crucial in the fight against impunity. As members of the affected communities, it is key that their voices are heard. If legal trials are to have a positive effect on Syrian society and potential transitional justice proceedings in the future, those affected must be able to have a sense of ownership with regard to such trials.

In the al-Khatib trial, it became clear that in proceedings based on the principle of universal jurisdiction, special attention must be given to the protection of witnesses. At the same time, witness testimony played a critical role: those affected could vividly describe the details of crimes they had personally experienced or observed, as well as provide information on the intelligence system and command structures, describe crime scenes and identify perpetrators.

Although the crimes in question primarily affected the Syrian community, it was initially impossible for most Syrians to follow the trial – the language of the court was German. Only after a constitutional complaint, which ECCHR supported, did accredited media representatives at least receive access to the simultaneous translations of the proceedings in Arabic that had been made available to the accused, as well as to the plaintiffs. However, ultimately most Arabic-speaking journalists continued to be excluded because they had not gone through the necessary accreditation process beforehand. It was a nonetheless a positive development that for both the trial of Eyad A and the trial of Anwar R, the court allowed the pronouncement of the verdict to be simultaneously translated.

Another point of criticism was that, in spite of multiple requests from civil society actors, the court refused to provide audio recordings of the proceedings. These could have furnished an important archive for commemorative, educational and research purposes for future generations.

Although enforced disappearance is one of the most emblematic crimes used by the Syrian regime to oppress the civilian population, it was not included among the charges – despite an urgent request by the joint plaintiffs.

In addition, the fact that both Anwar R and Eyad A had defected after working for the Syrian intelligence service, and had already disassociated themselves from the Assad regime before they were brought to trial in Germany, became a topic of controversial discussion. The court ultimately considered these circumstances as working in the favor of the defendants during the sentencing.

ECCHR supported 18 torture survivors, some of whom already gave witness testimony to the German Federal Criminal Police (Bundeskriminalamt) prior to the trial. 14 of them were plaintiffs in the al-Khatib trial and were represented by our partner lawyers Patrick Kroker, René Bahns and Sebastian Scharmer.

In addition, ECCHR initiated and supported requests aimed at increasing the involvement of the Arabic-speaking civil society in the proceedings. The constitutional complaint regarding access to translations of the trial, as well as the request to record the proceedings for future generations were among these interventions.

The trial in Koblenz is based on a series of criminal complaints concerning torture in Syria, which ECCHR and nearly 100 Syrian torture survivors, relatives, activists, and lawyers jointly filed as early as 2016 in Germany, Austria, Sweden and Norway.

Germany has taken on pioneering role in addressing international crimes at least since the al-Khatib trial in the Koblenz Higher Regional Court. One week after the verdict in the case of Anwar R was handed down, the Frankfurt Higher Regional Court initiated proceedings in January 2022 against the former Syrian military doctor Alaa M. The reason: strong suspicion of complicity in crimes against humanity committed by the Syrian regime since 2011. While employed as doctor, M allegedly tortured, killed and sexually abused people. The trial, in which an ECCHR partner lawyer is representing a plaintiff, could last several years – and it likely will not be the last trial on Syrian state torture.

As head of state, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has immunity and is therefore shielded from prosecution before national courts in third countries. However, as part of investigations that led to the al-Khatib trial, the German Federal Public Prosecutor has gathered evidence on potential crimes that Assad himself may have committed. This information could be used in the future, for instance, when he is no longer president, or if charges are leveled against him by the International Criminal Court or a UN special tribunal.

Torture in Syria on trial in Koblenz: A documentation of the Al-Khatib proceedings

Q&A: The al-Khatib trial in Koblenz, Germany

Dossier: Human rights violations in Syria: Torture under Assad

Transcript of the public prosecutor’s final statement on the case of Eyad A (German)

Torture in Syria: ECCHR’s work (Arabic)

Executive summary: Audio recording of the al-Khatib trial (July 2021)

Q&A Arabic: The al-Khatib trial on state torture in Koblenz, Germany

The principle of universal jurisdiction provides for a state’s jurisdiction over crimes against international law even when the crimes did not occur on that state's territory.

Show MoreThe UN Convention against Torture was adopted to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Show MoreCrimes against humanity are grave violations of international law carried out against a civilian population in a systematic or widespread way.

Show MoreWar crimes are serious breaches of international humanitarian law committed in armed conflict.

Show MoreSexual violence is defined as a violent act of a sexual nature. It is the deliberate exertion of power over another person, not an act of lust.

Show MoreThe principle of universal jurisdiction provides for a state’s jurisdiction over crimes against international law even when the crimes did not occur on that state's territory.

Show MoreThe law is clear: torture is prohibited under any circumstances. Whoever commits, orders or approves acts of torture should be prosecuted. This is set out in the UN Convention against Torture which has been ratified by 146 states.

Show MoreAttacks directed against civilians; torture of detainees; sexual slavery – when committed within the context of armed conflict, these and other grave crimes amount to war crimes as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. While the system of international criminal justice makes it possible to prosecute war crimes, in many cases those responsible are not held to account.

Show MoreEnforced disappearances violate a number of fundamental human rights and often serve to cover-up further crimes. In an effort to address the multiplicity of fundamental human rights violations involved, the United Nations drew up a Convention for the Protection of All People from Enforced Disappearances in 2006.

Show MoreCrimes against humanity – defined as a systematic attack on a civilian population – tend to be planned or at least condoned by state authorities: heads of government, senior officials or military leaders. In some cases, companies also play a direct or indirect role in their perpetration.

Show MoreTorture, executions and disappearances of civilians and indiscriminate bombings are only some of the crimes committed in Syria since 2011. ECCHR has been tackling crimes committed by all parties of the conflict since 2012 and is working with an international network.

Show MoreThe law is clear: torture is prohibited under any circumstances. Whoever commits, orders or approves acts of torture should be prosecuted. This is set out in the UN Convention against Torture which has been ratified by 146 states.

Show More